Waking up on a traditional chang ghar (stilt house) on a cool mid-November morning, all one hears are raindrops outside. But once outside, there is no actual rain. What sounded as raindrops was mist pouring down as droplets with sun dawn, from the tokou (Livistona jenkinsiana) roofs and from the vast green canopy covering the entire village of Namphake.

Namphake- an archaic village in Dibrugarh district of Upper Assam, about a kilometre and a half from Naharkatia, is home to the Tai Phake community, descendants of the great Tai race of Southeast Asia.

Archaic because the community chooses to diligently hold on to their original lifestyle and traditions over modern means and amenities. Preserved over 100 of years, this undiluted originality of the village gives outsiders a feeling of traveling back in time. This is summed up by a tourist who thinks, “It’s like I have time travelled to the Ahom era.”

Far away from their other Tai relatives spread across Myanmar and Thailand, the small Tai Phake community of Assam has a population of hardly 2000. Crossing over the Patkai hills around 1775, the Tai Phakes migrated from Howkong valley of Myanmar to the Northeast of India. For the next 50 years, they shifted to several places in the Northeast, in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Presently, there are nine Tai Phake villages in the Tinsukia and Dibrugarh districts; the largest being Namphake with about 70 households of 600 individuals, which was established alongside the Buridihing river in 1850.

However, this preservation of their Tai customs has not been easy. The community proudly states that their conversion to Buddhism about 1500 years ago has helped them in preserving their original practices- the Tai traditions, culture, language, and even their early religious practices alongside Buddhism.

The Tai Phakes follow the Hinayana sect of Buddhism, similar to those of the other Tai clans of Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Sri Lanka. The Namphake Buddhist Monastery was established in 1850 along with the village.

“Over the years, the Tai folk culture and Buddhism have assimilated and are helping each other to survive,” explained Paimthee Gohain, a resident of Namphake.

Struggles to retain the original

In Tai language, the village of Namphake is known as Man Tai. Namphake is derived from Namoni (lower in Assamese) Phake, meaning the Tai village which is geographically located lower than the other Tai Phake villages of Assam.

To the outsiders, the villagers speak in fluent Assamese, but amongst themselves the Tai language forms the main medium of communication. The Tai Phakes have evolved as a bilingual community- fluent in both in Tai, and also the Assamese language.

“We do not have any official institution to teach the Tai language. As a minority community, we pursue our education in the Assamese medium institutions nearby. There is no provision to teach Tai in these institutions,” says Gohain.

“The practice of speaking Tai at home has ensured that our children are introduced to the mother tongue at an early age. So, all Tai Phakes at least speak the language if not read and write,” he adds.

To keep the younger generation hooked to the language, periodic classes on reading and writing in Tai are put together by members of the Tai community. Presently, classes are held every Saturday and Sunday by a local resident knows as Ngi Than Hailoung.

But it’s not about the language alone. “The struggle is not just to sustain our language but also our attire that is woven entirely within the community. There is no market where we can procure our sheenn (ankle-long skirt), nang-wat (front open blouse), and chai-chin (a girdle to fasten the skirt)- worn by the women; and the phaa (lungi), sho (shirt) and Fa Ho (white turban)- worn by the men folk. Earlier every woman used to weave in our traditional loom. Now with girls are busy with education and job, and most have not learned to weave,” says Ngi Kya Weingken, another resident of the village.

With the number of women who acquired the art of weaving the traditional Tai attire dwindling, people of Namphake and the other eight Tai villages are entirely dependent on a few weavers who continue to maintain the tradition. But as demands are rising with a limited production, the prices of the Tai costume have soared much higher, further limiting the financially weaker section of the community from procuring these attires. However, these hardships have failed to deter the community from holding on to their tradition way of living.

A stroll through the narrow un-pitched lanes of Namphake gives an overview of the sparsely located stilt houses surrounded by greenery that seems untouched. The houses are made of bamboo and wood with a thatched roof of symmetrically placed tokou leaves, which is found in abundance. However, modernity is eroding the traditional ways of construction, replacing it with concrete, mainly due to economical feasibility and also in keeping with changing times and lifestyle. Moreover, stilt structures were preferred

mainly due to floods and hygienic concerns, which are no longer an issue.

Movement to establish and retain their identity

Crossing over to Assam in the latter half of the 18 th century, the Tai Phake people relocated to several places before settling in the nine villages of Assam. Although the community identifies themselves as Tai Phake, old records of the British era labelled them as Phakial. Even now, the community is known to many as Phakial.

Phakial is, however, considered a derogatory remark by the community, especially following its interpretation as ‘liars’ by many Assamese historians.

“Phaki in Assamese means lie. Many historians around the 1960s and 70s have interpreted it as ‘liars’, supporting that the Tai Phake community had previously lied or duped to acquire land and settle in the Northeast,” lamented Gohain. He has been working with the community for conservation and preservation of the Tai heritage.

“Since the 1980s we are trying to reinstate our true identity. We have written numerous letters and memorandums to replace the Phakial with Tai Phake in official documents,” he said.

As the usage of the language is gradually declining, and many Tai words are forgotten, the community has resorted to making modern songs whereby their folklore and several old words are incorporated. About five albums of 6-7 songs have been released so far. “The younger generation will listen to those songs and will at least put an effort to learn those words and tales,” added Gohain.

What is intriguing is that members of the same family use different surnames; most of the older generation through use ‘Gohain’, a surname ideally used by the Ahoms.

The nine Tai Phake clans have distinct titles. According to Gohain, when the community relocated to Assam, the indigenous people found it difficult or confusing to identify the members given their unique surnames that were mostly incomprehensible to the locals. To overcome this confusion, the nine clans decided to call themselves Koa Hai (Kao meaning nine and Hai is clan/branch of the Tai race). With time the Kao Hai got mispronounced and was called Gohain.

However, the younger generations have taken to writing their original surnames- Weingken, Thamoung, Sakhap, Hailoung, Chaohai, Pomung, Kheinlung, Tumten, Chaton, Maneing, and others.

Impacts of Buddhism in the Tai culture

Prior to Buddhism, the Tai Phake believed in an imageless spirit called the Chow Chau Phalong– a guardian spirit. A small shed or temple at one end of the Namphake village is dedicated to it. Even after conversion to Buddhism, their belief in the guardian spirit has continued unhindered.

So revered is the Chow Chau, after every eight days of the Tai calendar, two days are attributed to the guardian spirit. These days are called ghena, whereby it is believed that the Chow Chau roams across the village on a horse. In order to make free passage for the spirit, the Tai Phakes ideally remain indoors during the two days of ghena.

“We do not undertake any kind of outdoor activities like weaving, agriculture, foraging, etc (although the practice is a little less stringent nowadays). Even celebrations or joyous activities of any kind are barred. With due respect to this belief of the Tai community, any Buddhist festival that happens to coincide with a ghena is also postponed,” explained the villagers.

The chief priest of the monastery, Gyanpal Mahathera, also known as the Vante said, “According to us there are three main offerings that can bring ‘punnya’- the offering of the Buddhist texts, offering of the Sibor- the robe worn by the monks, and lastly to send the son(s) to the monastery even if for a short period to practice Buddhist monasticism.”

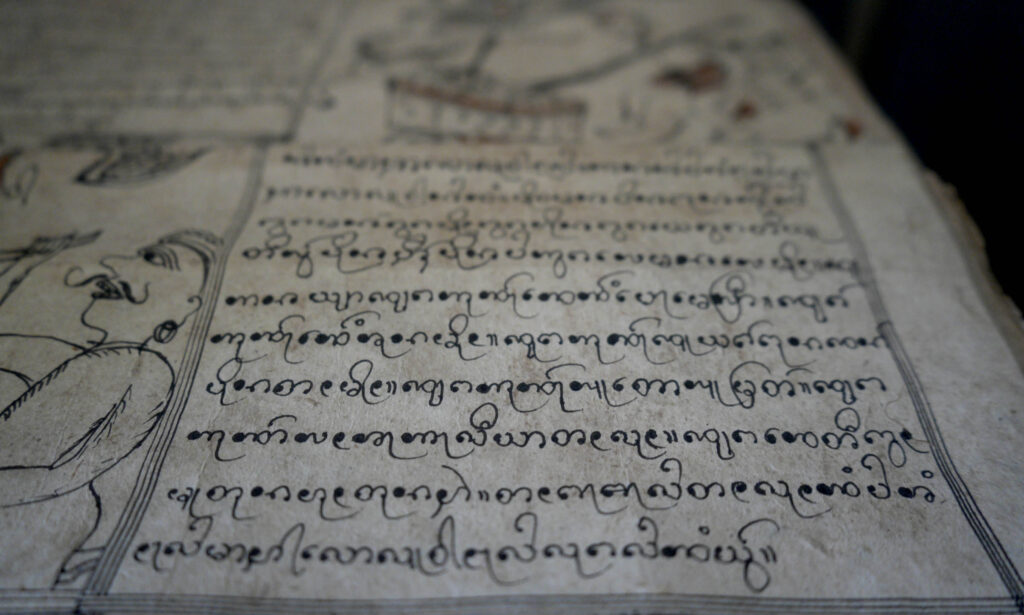

Migration of the first group of people also brought along the original texts to this part of the world. “These are in the Tai script and over the years people have copied these in their own handwriting to be donated during religious festivals. It is a way this practice has come a long way in teaching the younger people the Tai script- to read and write. We have about 400 books, but over 5000 copies of these books in total,” explains Gohain.

The other two forms of donations, of the Sibor and sending one’s son(s) to monasticism still continue. “These have knitted the community together. Also, all our Buddhist prayers and hymns are in the Tai language. All such practices have helped to keep the Tai Phakes’ closure to our Tai traditions, culture, and language for all these years,” said Gohain.

It’s intriguing to witness a community of just about 2000 individuals, far away from the original homeland, overcoming all challenges to preserve the Tai customs in its purest form. Unfortunately, with fast globalization posing more challenges than solutions, a substantial amount of the ancient Tai culture is on the fringes; likely to disappear and be forgotten in the next few decades.