Bangladesh and India share a lengthy international border measuring over 4000 kilometres, making it the fifth-longest land border in the world. This vast expanse of land runs through the States of Assam, Tripura, Mizoram, Meghalaya and West Bengal, and serves as a testament to the close ties between these two nations. From the bustling cities to the peaceful countryside, this border is a melting pot of cultures and traditions, with a rich history that dates back centuries.

The ‘border haats’ which are markets located on the zero line of the border between Bangladesh and India, have been instrumental in improving connectivity and above all, the markets have played a key role in improving the relation between the two countries.

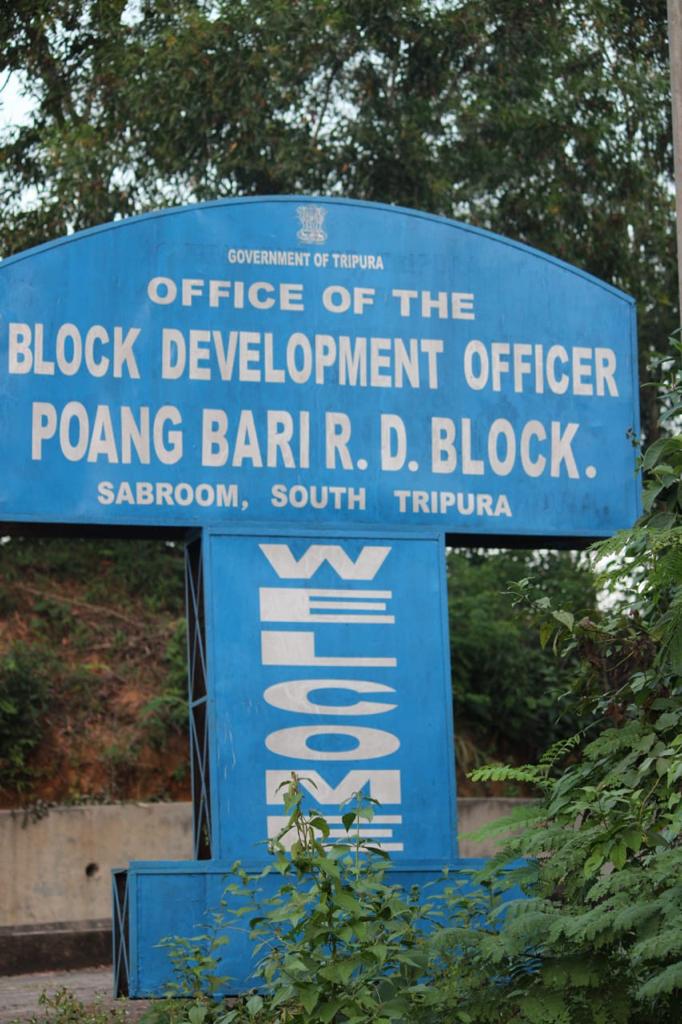

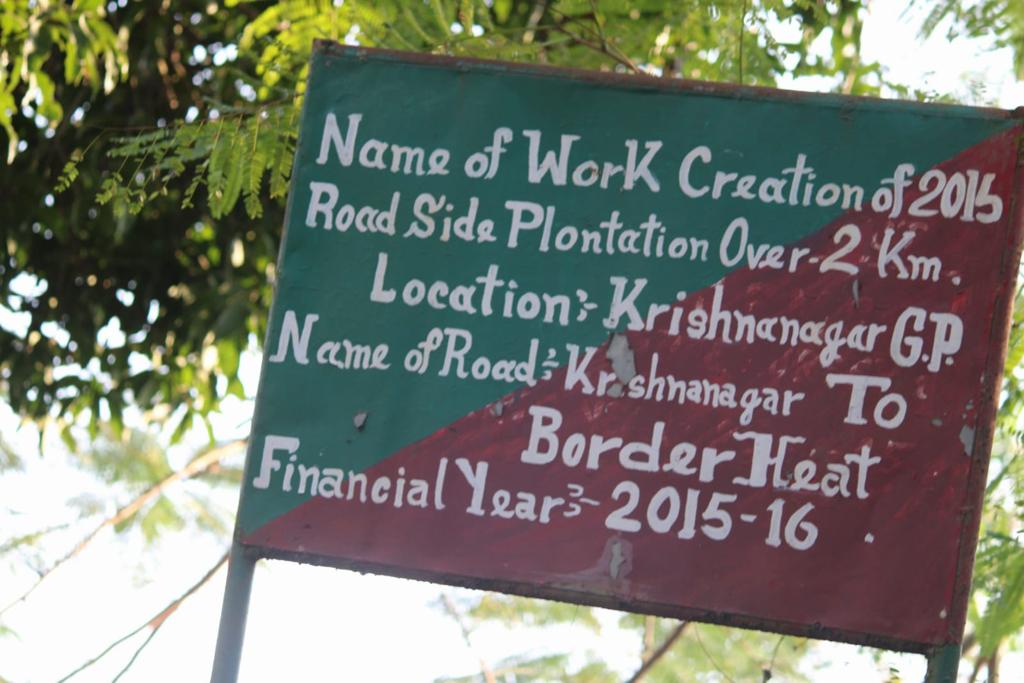

The first Border Haat identified as Chagalnaiyaa-Srinagar was established on January 13, 2015, in Sabroom, South Tripura. The markets, run by the government directly under MoDoNER serve as a hub between the two countries beyond borders to promote trade as well as a meeting place for the two countries to expand the economy and create job opportunities.

The relationship between international boundaries is more than just a trading or economic aspect, it also has ethical, linguistic and cultural implications.

Given that the border haats are an important source of employment and livelihood for the local communities inhabiting border areas, its closure for indefinite time will also have adverse socio-economic effects.

The Lockdown

When the lockdown measures were put in place, the closure of the border haats had a negative impact on the lives of the vendors who relied on these markets for their livelihood, leading to unemployment. The lockdown not only disrupted the flow of trade and commerce at these markets, but also had a significant impact on the financial stability of the vendors who depended on them as their financial difficulties caused family strife, domestic abuse, and divorce.

“No doubt everybody in the locality benefited from the opening of the border haat, it provided an opportunity to almost every household to engage in trading either as a vendor or vendee to meet the family’s financial needs”, Debashis Saha, a vendor and Secretary of the Border Haat Committee recalls a time when border haats provided a source of livelihood for the people who lived close to South Tripura’s borders.

Three years have passed since the international borders closed in Tripura’s Srinagar, and along with it the Chhagalnaiya, Bangladesh border haat in South Tripura. The pandemic outbreak and sudden lockdown that shut down the international border trade caused havoc in the lives of many traders in the area. [1] According to the Border Haat Committee Secretary, families eventually declined to poverty as a result of bank loans. “I took out a loan for the business but I still owe Rs. 12 lakh and I am making my payments”, he added.

Senior vendor Ganesh Chandra Das recalls how they were informed about the lockdown and closure of the border late one night. He says, “It was very sudden; we had previously purchased items from wholesalers in far-off towns and had everything prepared for sale for the next day. Vendors purchase goods from wholesale markets due to the great demand from Bangladeshi consumers; as a result, the unanticipated shutdown caused the vendors to suffer considerable losses.”

A vendor who identified himself as Subhas claimed that as a result of the protracted closure, he was compelled to discard the expired products, some of which were used for self-consumption, and resell the remainders for a very low price. “I took up a loan from the bank to expand my trade as I could see success in it,” he said. The lockdown forced him to lose a lot of money since he is now paying back the installment.

Ramesh Debnath a 38-year old local resident received a vendee permit after losing his job as a teacher. He was able to provide for his family through the income from his new trade. He would purchase items from the haat for a fair price and resell them to buyers who were stationed outside of the capital city and other town areas for a profit.

However, the closure of the markets led to a complete financial collapse for Debnath and forced him to turn to informal trade in order to recover losses. Despite the challenges, Debnath did not give up. He continued to reach out to Bangladeshi traders to continue supplying products helping to eventually recover his losses.

Bikram Tripura, an indigenous tribal vendor from Poangbari has a similar story to tell. His financial crisis after the lockdown compelled him to work as labourrer to repay a loan of almost 2.5 lakh. The lockdown measures had a far-reaching consequence for many vendors at the border haats. For vendors like Khalid and Ganesh, the closure of the haats has meant more than just a loss of income. It has also meant the loss of a sense of community and connection, as the haats provided a place for them to come together and interact.

Other Challenges

While some of the sellers and buyers used their money in informal trade activities, concerns about permits were raised by the committee secretary, who noted that often the number of Indian vendors inside the haat exceeded those from Bangladesh.

This disparity in the population of vendors affected Indian sales because there were fewer customers from Bangladesh and it was clear that Indian consumers did not prefer Indian goods. Besides, with a defined open time of 8 am to 4 pm, the prolonged delay for entry passes interrupted the business and vendors occasionally received entry very late and were forced to leave without making a sale.

Theft has also long been a major security concern in the haats. A young tribal seller named Naiphang Tripura claims that thieves and robbers take advantage of the haat’s lack of security. The vendors often act on their own as a result of insufficient security measures, which they say compromises with the haat’s main objective of providing a secure trading environment.

The other key challenge is that male dominance at the haats has impacted the participation of women which is antithesis to the primary goal of encouraging women traders to participate in income production through border haats. This is seen by many as a contributory factor for the significantly low number of women traders.

Significance of border haats for local residents

Given Tripura’s size, the third smallest state in North East India surrounded by Bangladesh on three sides on the North, South and West, the 856 km border haat is an important lifeline. Apart from Tripura, two additional border haats have been established in Meghalaya, at Kalaichar and Balat. A total six border haats are in the pipeline, with four more set to come up in Tripura alone.

Local traders have the edge in these border haats as rules restrict out-station traders for entry without prior approval from the government. A number of 57 vendors, including 27 from both India and Bangladesh, were allowed to sell inside the haat.

The most popular products, according to field data from India, are cosmetics, branded infant food like cerelac, or horlicks, and other branded stationery items. Vegetables and a variety of fish draw customers from India. Indians sourced dry fish and bread in great quantities. More demand is being made for India’s value-added products rather than achieving the haat’s primary goal of marketing locally produced goods. This simply highlights the lack of market for the local raw materials. Setting up medium and small-scale enterprises in Tripura’s border regions to transform raw materials into marketable value-added products will have a bigger impact on meeting the demand and boosting the local economy.

The government devised laws and regulations to ensure seamless operation, and a committee was established to govern the haats. The haat’s first three years were marked by few regulations and a friendly atmosphere where locals benefited with buyers from across borders, which increased transactions, and there were few restrictions for tourists to obtain entry passes. However, since 2018 tougher regulations and admission requirements have been introduced for tourists.

Under the current system of limited vendor quota, measures were undertaken to provide better livelihood chances to as many people as possible by maintaining a ratio of one to three, or three helpers for every vendor permit. Every household with ration cards under the Poangbari rural development Block were entitled for a vendee pass. The vendor received a permit to purchase items from Bangladesh and sell them in India. The pass is valid for three years and renewal at the block office for Rs. 300.

In the first three years, the weekly opening day profit for the sellers ranged from Rs. 20 to 50 thousand. The system enforced stringent trade restriction laws, allowing each vendor to sell goods worth a maximum of Rs. 4 lakh on each ‘open day.’ Similar rules were applied to fish buyers, with limits of a maximum of 5 kg per buyer. Buyers of other goods were not subject to such restrictions.

However, change in rules, particularly the introduction of severe regulation through customs checks since 2018 has considerably worsened the plight of merchants. Most merchants complained that “fines being issued for minor offenses as opposed to the earlier days since the opening of the haats.” Local sellers feel that, “custom screening should be done correctly at the gate rather than checking on arriving inside,” as such arrangements “forced people to pay a fine in order to avoid the customs officers’ harassment.”

Need for reopening the border haats

It’s been a while since the border haats have been closed and the familiar sight of the bustling market with vendors busy setting up their stalls as the first rays of sunlight begins to appear over the horizon between the borders separating India and Bangladesh. These markets are more than just a place to sell their goods, and services. For most people they are a lifeline.

The closure of these markets has had a significant impact on the lives of the local residents who have been waiting patiently to see the reopening of the markets. For now, they are filled with uncertainty about what the future holds and how they will be able to rebuild their lives and livelihoods.