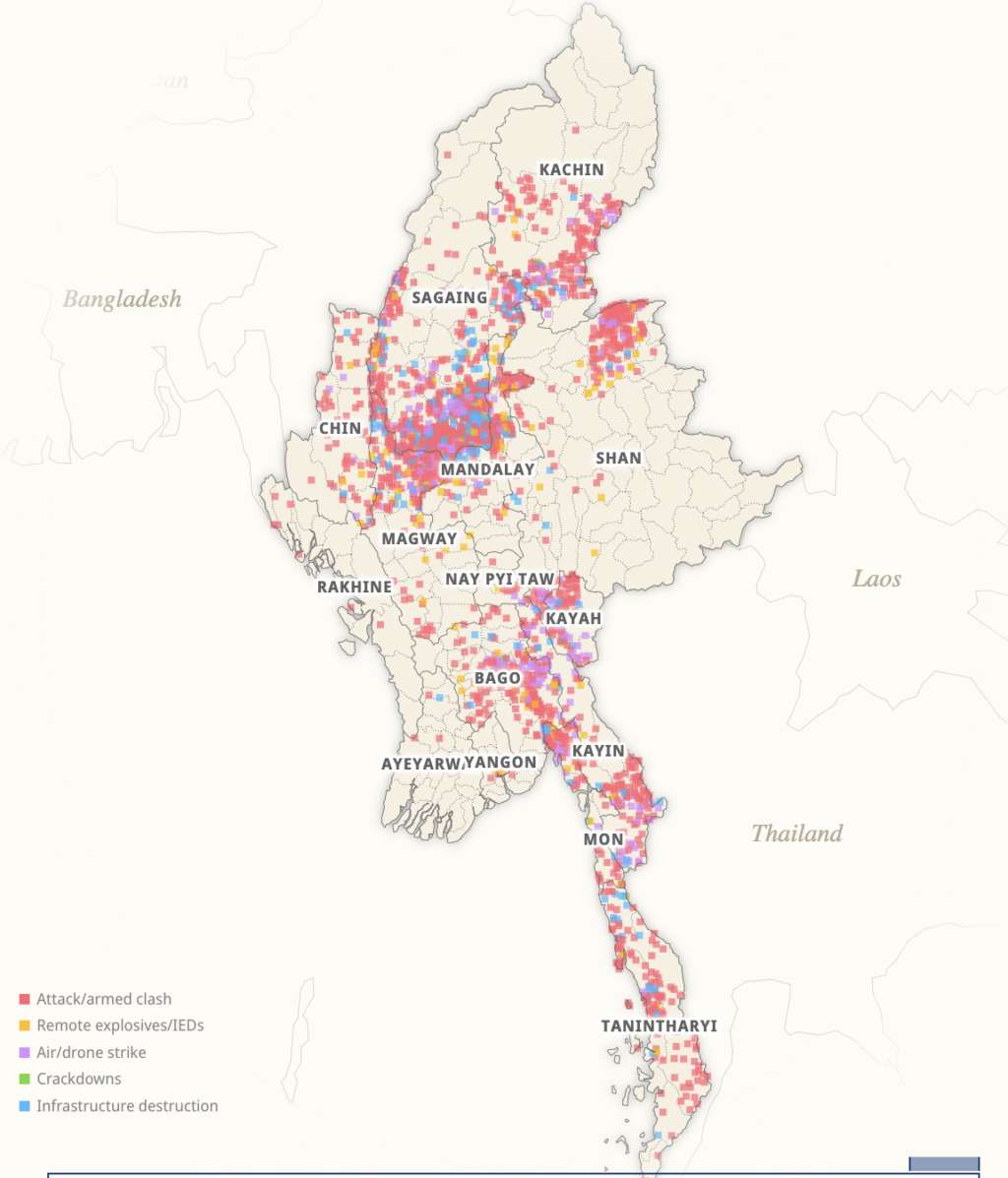

As the recent offensives by the Resistance Forces in Myanmar have had a significant impact on the military junta, making it abandon some of its strategic positions in the north, east and western parts of the country, the common question being asked is whether these developments mean an existential threat for the State Administrative Council (SAC) headed by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. These are still early days and given the complex conflict dynamics of Myanmar, there are no clear signs yet to write off the junta rule.

There is not a shadow of doubt that the Resistance Forces have made vital gains, by capturing key cities and townships. In fact the resistance movement against the military junta led SAC which started after the February 2021 coup has been reenergised by the well-coordinated offensives launched by the Three Brotherhood Alliance in the northern Shan state since October 10. The offensive by the alliance which comprises of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) a predominantly Kokang group, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Arakan Army (AA), has infused fresh energy into other armed resistance groups prompting them to launch relentless attacks on the military junta in other parts of the country.

The offensive launched by the Three Brotherhood Alliance codenamed ‘Operation 1027’ has been extremely embarrassing for the Burmese military establishment, to say the least. Close to 200 vital military bases have fallen to the ethnic armed alliance and major townships like Muse, Hsipaw and Hseni townships and Kunlong (a major military strategic base on a Myanmar-China trade route) have been taken over by rebel groups. The last stronghold which is Laukkai – the regime’s headquarters located here – a key junta stronghold in the Kokang self-administered zone, near the Chinese border has been surrounded on all sides by the MNDAA. Laukkai is a notorious nest of online and offline casinos and telecom scams.

Notably, the offensives in the Northern Shan state is taking place at the site of the proposed China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), a pillar of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Not only has the military junta been taken by surprise by this sudden attack on its bases, its impact in other neighbouring areas, such as Sagaing and the Chin state has been unprecedented so much so that for the first time in Myanmar’s history of conflict, its military personnel had to run across to India to save their lives. Reports of 41 junta men fleeing towards the Indian side in Zowkathar along the India-Myanmar border on November 13 and surrendering before the Mizoram police was all over the news media. They have been all flown back by the Indian armed forces to Myanmar.

Sources in Rakhine and in other parts of the country suggest that with increasing offensives similar escapes by the military junta soldiers are possible across the international borders with Bangladesh and Thailand. There are more soldiers who are said to have escaped across to India near Sagaing.

A Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) report states that a total of 326 soldiers, police and militia members have surrendered to resistance forces across Burma since October 26. Around 70 civilians have been killed and over 90 have been wounded with more than 200,000 people displaced from their homes, the report adds.

The Northern Shan Offensive and the ‘China game’

These developments have led to a flurry of commentaries and speculations on whether the military junta was turning a corner and the resistance movement led by the National Unity Government (NUG), which is formed by elected representatives who were ousted in the military February (2021) coup would soon bring the country back to civilian rule. The NUG and some senior functionaries of key ethnic armed groups have hinted at such a possibility, a Rakhine leader even saying, “wait and see how we reach Naypyitaw soon”.

However, there are many others who think “it’s too early to tell,” and that “there are many challenges ahead which would be critical if the military has to be ousted.” Let’s start with the developments in the northern Shan state bordering China. Firstly, the offensives by the Brotherhood Alliance would not have been possible without endorsements from Beijing. The offensives which have been carried out on key junta defence installations and security posts are all strategically located close to the China border.

Though it is arguable whether China gave the green light to the ethnic armed alliance, the fact remains that China did not resist the operation, but only express concern on the spillover effect of the conflict on its side of the border.

While for the Chinese, the offensives paved the way for a more targeted crackdown on the online scam and money laundering networks inside the Kokang region, for the MNDAA this was a great opportunity to take on the military junta and display its prowess.

The same applies to the TNLA which has been fighting its own territorial battle. Thus, the conflict dynamics in so far as the ethnic armed groups are concerned, which are rooted to territorial control more than anything else, have not changed much. The present developments which feature similar coordinated attacks by opposition forces in other parts of the country only adds a new dimension to the conflict narrative in Myanmar.

Shan State and the complexities of conflict

The Shan state which shares border with China in the north and Laos and Thailand in the east and south respectively, has seen some of the bloodiest violence between various warring ethnic groups. The MNDAA and the TNLA, have both been waging their own battles against rival groups to hold on to areas in the north on which these outfits have staked claim since long. The MNDAA which split from the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in 1989 are mostly ethnic Kokang – a Han Chinese minority – has sought to control areas around Laukkai the capital of the Kokang Self Administrative Zone situated along the Chinese border. The Ta’ang or the Palaung which forms the TNLA on its part has been fighting for what it calls its “homeland” in northern Shan state.

The TNLA has been involved in inter-ethnic clashes with other Shan groups like the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) and the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army (SSPP/SSA). Amidst its anti-junta offensives Ta’ang fighters have both aligned and engaged in fierce fights with members of the SSPP, the latest being November 7 when armed cadres of both sides clashed against each other. The TNLA’s expansion has also created tensions with other ethnic armed groups and non-Ta’ang communities in northern Shan State. The group’s ambiguous political positioning since the coup reflects the complex environment in which ethnic armed groups operate.

Many Myanmar watchers believe that the recent blitzkrieg by the TNLA and the MNDAA in northern Shan could increase inter-ethnic tensions. A Crisis Group report indicates that with the launch of Operation 1027, there has been a shift in the power balance which has alarmed Shan communities and armed groups. Rival ethnic groups are wary of the Ta’ang and the Kokang gaining strength and expanding their territory into ethnic Shan areas. Many local Shan intellectuals have openly questioned the silence of the two ethnic Shan armies the SSPP/SSA and the RCSS.

Many Shan residents who support a democratic future for Myanmar, are not convinced with the recent offensives by the Three Brotherhood Alliance. They fear that the goal of the Ta’angs and the Kokangs to set up their own autonomous states, would displace Shan ethnic groups from their land. Local writer and commentator Hurn Kayang questions the effectiveness of the policy of silence of the two Shan armies, which represents the “interests of the people.” He, like others, feel that the conflict situation has worsened after the recent attacks with people enduring the suffering,

The conflict has caused numerous casualties, injuries, arrests, and the displacement of over 50,000 people, with ongoing artillery shelling and airstrikes further exacerbating the situation.

However, what also emerges from such questions are the positions these groups have taken vis-à-vis the coup and the peace process in Myanmar. Both the Shan armies have not engaged in any decisive direct confrontation with the military junta since the February 2021 coup. Shan ethnic groups like the RCSS has been meeting the Burmese military leadership even after the coup, the gesture born out of its belief that the conflict can be resolved through the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) which was initiated by the military junta led government under General Thein Sein on October 2015.

Rival Shan ethnic groups like the SSPP have clashed with the Burmese military junta but have also kept doors open for negotiations with the latter. Reports have it that leaders of the SSPP/SSA recently travelled to Naypyidaw to meet regime leaders. On the other hand, SSPP/SSA along with the TNLA and the MNDAA are part of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), led by the powerful the United Wa State Army (UWSA). Others like the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) which controls the Mong La area in the eastern Shan state are also part of this seven member grouping which has close ties with China.

Although the bloc has refused to sign the NCA, it has responded favourably to Beijing whenever the Chinese Communist Party leadership has convinced it to engage with the military junta. Soon after the coup, China facilitated a meeting between the leaders of the FPNCC and senior military junta leaders at the NDAA’s headquarter in Mong La. Quoting a “senior leader” of the Northern Alliance (which includes the KIA, MNDAA, TNLA and the AA), a report in Frontier Myanmar claims that the military regime pressured the FPNCC representatives “to sign a peace deal,” which they rejected. The report, however, does indicate a schism within the FPNCC caused by the military regime’s ploys, so much so that the UWSA, the NDAA and the SSPP are said to have become more willing to negotiate with the junta. The above groups are said to have met the SAC chair General Min Aung Hlaing twice in 2022.

The UWSA which has been demanding greater autonomy of the territories within their control entered into a ceasefire with the Burmese junta since 1989, following which it has refrained from engaging in any direct conflict with the military junta. Consequently, other groups like the SSPP, and the TLNA which have close ties with the UWSA, have been measured in their response to the pro-democracy movement.

Further, barring the spontaneous attacks by other EAOs and the PDFs following the Three Brotherhood led offensives, there were fragmented views from the FPNCC alliance partners. For example, the KIA and the SPP/SSA pleaded ignorance about receiving any prior information about Operation 1027.

On the other hand, the MNDAA and the TNLA’s expansion into areas like Monekoe and Kutkai respectively, may not go down well with the KIA which consider these areas as part of their Kachin Sub-State. Local Myanmar observers seem to believe that the KIA’s actions are “distinct” from Operation 1027. The KIA’s attacks against the military junta are seen as part of the outfits goal “to expand its control.”

However, what is also true and what equally adds to the complexities is that the KIA, which is the second largest force in the FPNCC has often refused to align with decisions of other groups like the UWSA and NDAA to toe China’s lines. Instead, the KIA has been mostly engaged in supporting the NUG through trainings to PDF cadres and has even joined forces in some of the attacks which have been launched in and around the Sagaing division.

The AA has tried to portray ‘Operation 1207’ has one which has evolved into “a nationwide operation.” AA spokesperson Khaing Thuka has exuded confidence about “a common goal” approach which would bind all the forces together. Yet there remain questions on whether the Three Brotherhood Alliance or at least the MNDAA and the TNLA be willing to build on the gains made from the recent offensives by aligning with new groupings like the 3KC (which has the KIA, Karenni National Progressive Party/KNPP, Karen National Union/KNU and the Chin National Front/CNF) as well as the NUG/PDF.

The question to consider is the impact of these above-mentioned challenges before the pro-democracy forces both within and out the NUG banner in their mission to provide an alternative to the junta led rule in Myanmar. The existing conflict dynamics in the Shan state could also help to explain why building a countrywide anti-regime alliance has proven to be difficult.

China’s role as the meditator?

China has supported the junta since the coup but has at the same time held on to its links with the EAOs. The recent attacks which also includes a possible MNDAA takeover of Laukkaing, a crucial junta stronghold in Kokang, would indicate a willingness on the part of China to let the situation be until it achieves its goals – to successfully carry out “swift attacks” on crime and money laundering gangs in Myanmar. Incidentally, these cyber scam networks and the associated crimes are controlled by influential Chinese syndicates all across southeast Asia, which has been an embarrassment for Beijing and hence the crackdown.

Myanmar watchers believe that Beijing will take a call any time soon by stepping in to bring about a semblance of clam in the Kokang region and other parts of northern Shan state, “which works to its larger interests.” This especially after the death of the telecom scam ringleader Ming Xuechang, also a former member of the Kokang Self-Administrative Zone, committed suicide by shooting himself on November 16 while being arrested in Laukkai.

Besides, the telecom strongman’s son and granddaughter were arrested and handed over to the Chinese authorities. This also follows a statement from the China’s Ministry of Public Security on Tuesday that more than 31,000 suspects involved in telecom fraud cases have been transferred from Myanmar to China.

The results of the present crackdown and the gains from it might make Beijing introspect the recent escalation of conflict along its borders and find what Myanmar experts say is “a temporary cessation of violence before things go out of control.” A Crisis Group report is of the opinion that China could well intercede in this manner should the MNDAA manage to secure control of Laukkaing and the rest of the Kokang zone, or if the conflict drags on and threatens an extended period of instability on its border.

Clearly Chinese authorities do not want the conflict to escalate beyond a point, something which it may have miscalculated, especially given how the Brotherhood Alliance is still pushing ahead with its offensives towards Laukkai the capital of the Kokang Self Administrative Zone. On Saturday, military drills were held by the China along its borders with the Northern Shan state, which hint at a potential Chinese push for normalcy.

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Southern Theatre Command has said that it will conduct a series of “real combat training” and drills along the Chinese side of the China-Myanmar border, “to test the rapid maneuverability, border sealing and firepower capabilities of locally positioned troops.” Chinese military experts have termed the drills as a “key signal” from China regarding deteriorating situation in northern Myanmar.

Military experts in China are of the firm belief that Beijing would not want to compromise security on its border, which also hints at a potential and more targeted intervention. In fact China has sent out messages to the Myanmar junta to ensure security on the border, its Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning making clear that Beijing is working towards a cease-fire, dialogue. The escalating conflict in northern Shan state and its impacts across the Myanmar is a cause for worry for China as it hampers its over USD 10 billion trade and commerce, surging investments and the push for BRI. But there is also something else which has been more worrisome – which is the advances made by Myanmar’s NUG/PDF which China views as a largely Western influenced and which could jeopardise its own interests in the event of a defeat of the junta.

Thus, when the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson demanded that Myanmar take practical steps and effective measures, it would appear to convey a certain urgency from Beijing. Instances in the past are testimony to the kind of influence Beijing has wielded on the conflict theatre in Myanmar, particularly so when it comes to playing the mediator, negotiator and even spoiler between the junta and the ethnic groups.

In October 2015, Beijing influence saw groups operating in the north, prominent among these are the UWSA and the KIA staying out of a military backed government led peace process. Similarly, in July 2018 during the National Leader Democracy (NLD) led civilian government, China played a key role in playing mediator as part of the 21st Century Panglong Conference meeting held near the Chinese border between the government and rebel factions. In the same year on September, China facilitated a meeting in Southwest China between the Union Peace Commission with the Northern Alliance bloc.

Moreover, an FPNCC statement released in March 2018 said that it sought further support from China in Myanmar’s peace process and that China’s positive involvement in Myanmar’s peace process has become more important and cannot be averted. China has played multiple roles to brokering peace which goes back in time. China intervened in February 2013 and organised peace talks between the KIA and the Tatmadaw.

The Burmese junta which faces aggression on all fronts post ‘Operation 1027’, has a strong ally in China and countries like Russia with which it has been strengthening its ties. Besides, a number of countries in the region, including those in ASEAN which have continued to trade with it, which may give it the sufficient reasons to hold on to power. It also has effective airpower, airports, seaports and control over major big cities like Yangon, Mandalay, Naypyitaw, Pyin Oo Lwin and Meiktila the last being amongst its strongest military installations to mention a few.