“When I was little, I would hear my father recite the ritual chant close to the hearth and sleep to the sound of my father’s voice dissipating into a lullaby”, says Dobom Doji, a folk singer from Arunachal Pradesh. Kendo Doji, his father, is 68 years old, a shaman from Doji Village, Aalo. Shamans in Tanii (descendants of Abotani) clans occupy a central religious position in our societies. Recounting myths and using a language understood by a few, a shaman sings and uses chants to engage the spirits. Since his formative years, Kendo had replicated his predecessor’s affection towards the practice of shamanism and grew up to follow suit. At present, along with his shamanistic duties, he recounts histories and pens them in a script he conceived himself. Many of these histories and stories recuperate in Dobom Doji Collective’s folk music. “Asi Noru Eh”, a DDC original, was written by Dobom’s father. He detailed the rituals of benediction to the deities for the conduct of a successful event in his lyrics. The music video depicts how Galos performed these rituals to bring fortuity in events such as hunting, childbearing, etc.

Surely, numerous symbolic claims to indigeneity in the present times have discouraged traditional practices in their entirety. Shamans, along with their vast repository of verbal traditional knowledge and practices also stand precarious. Where traditionally, chants echoed the euphoria of festivals, attention has now shifted to grand symbolic tangible gestures of our culture, mostly limited to traditional attire and food. In this critical juncture of seemingly losing traces of the knowledge that made us, Dobom Doji Collective (DDC) with their adaptation and rendition of folk songs are reviving our lost prayers.

Dobom is a converted Christian despite his father being the clan’s shaman. However, any juxtaposition of their religious ethos was irrelevant. Dobom said, “My father always told me, you choose your religion but your traditions and customs are inherent. Remember that, we are born of extraordinaire culture and we ought to keep them alive.” This, he says, resonated over the years. Eventually, when he released a rendition of the popular Galo folk tune “Jimi Ane”, originally sung by Jomnya Siram on YouTube, it gained massive popularity and his work began to be appreciated widely. Audiences invariably loved the shamanistic tonal quality of his voice. This further roused his motivation to keep folk music alive.

*According to Galo cosmology, the world was created by Jimi Ane (Ane means mother in Galo), regarded as the Supreme Being. The history of the Galo tribe therefore in the original genealogy essentially begins with her (Jimi Ane).

Dobom was earlier a member of the band called “Brickcity Boyz”. However, the band disbanded in 2019 and after a two-year hiatus, Dobom Doji Collective came to be. They first performed together as a band in 2022 during BasCon 5.0, in Basar. Since then, they have performed in numerous other events and music festivals such as Siang Fiesta 2.0, Goonj Arunachal, and IndiaVision Mandala Festival, Dirang. Their forthcoming performance will be at the “Orange Festival of Adventure and Music” (OFAM), Dambuk, also the first-ever Adventure and Music festival in India. The band will perform alongside popular artists such as Bombay Vikings, Ritviz, and others.

“I am content with our work. My bandmates are the best. It has not been an easy ride but we love what we do and enjoy doing it. This feels like my purpose. My father’s encouragement has always been a driving force for my music career, and it is to him that I owe my everything.” Dobom explained.

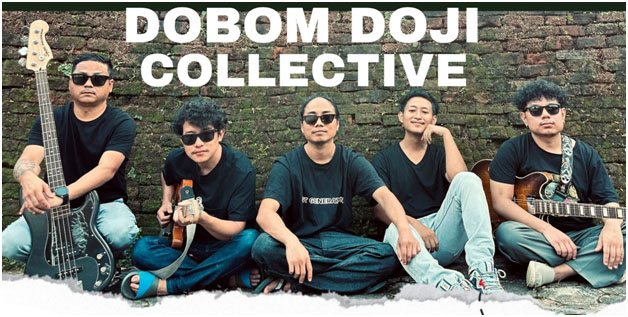

Dobom Doji Collective is a folk fusion, 5-member music band from Arunachal Pradesh. Inspired by the tonal quality of his father, Dobom emulates a similar musical tone and pitch as the frontman of the band. Joe Kabak plays the lead guitar, Nyaamo Jini on rhythm guitar, Papu Dolo, a former member of Alien Gods on the bass, and Samuel Laye on drums. Collectively, they have been performing together for less than a year, nevertheless, the band’s popularity has been evident with the audience’s appreciation. Their work has garnered the attention of the public who appreciate folk art and tradition. Their songs at large reflect the saga of our ancestors, the lives they lived, and the myths in them, created. These myths and stories represented the absolute about primordial times.

In traditional societies where only the sacred has value, the first appearance of the sacred is contained in these myths. Mircea Eliade, historian of religion concurs with the idea of “Nostalgia of Origins” wherein he argues that, “It is prevalent among traditional world religions for a desire to return to the ‘Primordial Paradise’.” referring to a longing for a future that is reminiscent of the past. Therefore, these histories appear time and again restructuring our culture and this overlapping process ensures remedial corrections to contemporary issues at hand.

Culture as we say, is most widely made up of ‘tangible’ and ‘intangible’ aspects. Tangibles are those that are material such as food, clothing, etc. Intangible forms of culture include our customs, traditions, narrations, and oral histories. Although the definition of folk art is not unique, it can be said that it is a form of artwork produced by groups within the larger cosmopolitan society; primarily isolated from the fast-paced notion of contemporary city life. Attempts have been made to conceal folk art in its pristine form however contemporary realities leave little space for older traditions to proliferate in ways attended before. Prayers and chants now slowly recuperating into widely accepted forms of cultural expressions as folk songs; engages and energizes the audience in a way that prayers did many decennials ago.

Manorama Sharma in his book, “A Comprehensive Study of Indian Folk Music and Culture” states, “Folk traditions are contributions of cultural variety, agricultural methods, communal groupings, religious and social organizations, festivals and seasons. These activities and the emotions involved need to be conveyed by humans via sound.”

However, since social change is never a linear process and complexities designate the socio-cultural interactions between people; any change is, therefore, a by-product of these interactions and vice-versa. Such interactions are a dialectical process of dialogues, debates, actions, and reflections, occurring more often among indigenous expressions of culture. Traditional folk songs are one such form of communication that retains the dialectical process and ascertains proximity between people and their cultures.

E.H. Carr writes in “What is History” that “History is a continuous process of interaction between the historians and his facts, an unending discourse between the present and the past, a dynamic, arguing process.” simplifying what had been said before; cultures and humans are production and reproduction of each other; one engendering the other and in turn creating possibilities in the understanding of cultures. Thus, folk songs have remained a crude representation of any tribal culture. All events begin and end with melodies of traditions. Significantly played and sung during events such as weddings, baby showers, housewarming, and even funerals; folk songs are relegated to the way of life that has remained unchanged ever since. These songs are often reminders of the interaction between humans and nature; a recollection of indebtedness to our ancestors for their struggles. However, not all folk songs are memories of the past, many offer insights into anticipations of the future; changing over time and reflecting societal norms and values it encounters.

Tradition, therefore, as the basis of cultural preservation is a complex process. It requires constantly re(interpreting) what we understand as ‘traditional’ and worthy of ‘preservation’. As such, newer renditions of these expressions become essential in small-scale societies, where oral literature was earlier transmitted and inherited in the form of folklore and songs. As Eugeen Roosens, an anthropologist writes,

“Ethnic groups are affirming themselves more and more. They promote their own new cultural identity, even as their old identity is eroded… To be sure, the process of acculturation will continue to cause many cultural differences to fade away. Nevertheless, new cultural differences will be introduced, sometimes in a deliberate manner.”

Today, DDC performs folk songs incorporating Western musical instruments. Contrary to how folk songs were earlier performed with isolated vocals; guitars, bass, keyboards, and drums are now widely used. It caters to a wider audience transcending state and national boundaries, imminently engaging audiences with genres and tunes they are familiar with.

DDC says, “To keep folk music alive, we have to respect the present epoch and move along with it.” In today’s time, with the growing popularity of folk songs, it is evident that folk art stands the test of time and remains a testament to the fluid nature and expression of indigenous identity.

Watch here: Dobom Doji performing live

Indigeneity cannot be materialized as something static. Indigeneity is expressed in reformation as well as in change. Traditional religions all over the world have been institutionalized in some form or the other to prevent their death. Similarly, like any other form of culture, religion or folk art requires alterations to survive. Because folk art and music do not have prescribed rules, they lend themselves easily to fusion and mixing. “Oral traditions offer room for improvisation. Therefore, any eclectic vision of folk music renders subjectivity and personality. The songs can feel to be ours again by singing it the way we love to.”, says DDC.

Folk songs also incorporate forms of cultural expression such as language/ local dialects that are seemingly dissipating into private conversations at home. Termed as ‘endangered’, some dialects of Arunachal Pradesh cast an inadvertent and inevitable tone to the dissipation as if confirming it to be a product of unfortunate but impersonal juxtaposition of inevitability. However, such impositions are not merely glorifying the external influence and occupation of foreign languages but also actively impede any progress in saving traditional languages. This is equivalent to providing sanctuary to the colonial violence behind the decline of the many indigenous languages over time. Cynthia Groff, a linguist opines, “To legitimize a language, one has to acknowledge its existence.” DDC by actualizing traditional folk tunes into present genres is one among the many who are contesting modern barriers to our customs and traditions. “When people heard our songs, it evoked a sense of curiosity as to what our songs inferred. A hum here and a hum there, although slowly but steadily feels like a folk revolution is imminent.”, says DDC.

Language creates the world we inhabit and as is, it is an external manifestation of our mind. Our thoughts and expressions are limited to the languages we speak. As it is, indigenous languages and dialects offer a multitude of expressions. Every emotive expression is communicated in indigenous dialects. Therefore, to revive our chants, our myths, our histories and our dialects in the form of folk songs is an active endeavor toward the preservation and propagation of our culture and traditions. Their recent release “Melo Jajine”, is a rendition of an old classic by Moge Doji narrates the story of migration. It enunciates the profundity of our forefathers; their struggles, and eventually their settlement in the hills. The song rekindles the spirit of storytelling as an integral part of our culture. Thus, a fluid transposition of traditional elements into contemporary expressions does not warrant the dismissal of culture. Indigeneity is independent of change. More often so, change engenders indigeneity in ways customs and mores would not.

Therefore, to say that culture is slowly dissipating would be an overstatement, and although there are aspects of traditional culture that are dying, its death warrants the need to advance our culture in forms acceptable. Because, how long can any community or a group clench onto something that doesn’t materialize into contemporary needs? And who is to say that culture and traditions are finite? We need to understand that identities and such indigeneity are fluid concepts and so is the need to transmute our culture with it. Therefore, in an attempt to keep our traditions and culture alive, DDC reviving the lost prayers of our forefathers will memorialize our ancestors’ spirits and ethos in us forever.