As Nobel Laureate Professor Mohammad Yunus attempts to stabilise his interim government in Bangladesh, the spectre of an “Islamic state” has begun to loom ominously over the nation. The very foundations of the secular state that Yunus seeks to fortify are being threatened by the resurgence of Islamist forces, eager to seize power and impose their vision of an Islamic republic.

Reports from local media paint a troubling picture. On August 25, the Jammat-e-Islami of Bangladesh convened a critical meeting in Dhaka with the country’s top Qawmi scholars. The agenda was stark: a call for the establishment of a state governed by Islamic laws. The voices advocating for this were not just a few radicals on the fringes; they included prominent members of the Hefazat-e-Islam and influential Islamic scholars who have long held sway over significant segments of the population.

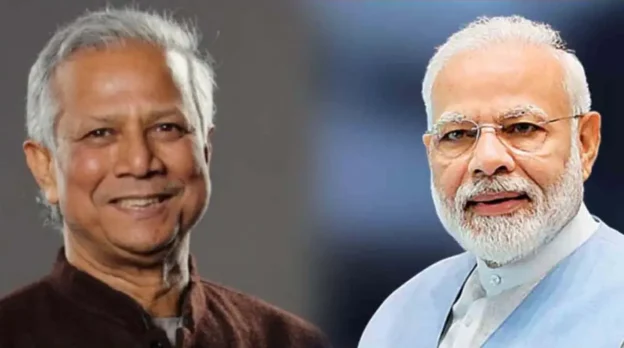

This push for an Islamic state runs counter to the ideals that Professor Yunus has hinted at, even if he has been careful with his words. Although Yunus has rarely used the term “secular” in his speeches, his calls for reforms, unity, and the protection of minorities, including Hindus, signal his commitment to a Bangladesh that remains democratic and inclusive. His vision, however, is being challenged by those who see this as an opportune moment to redefine the country’s identity.

These are still the early days of Yunus’s leadership. Since taking on the role of advisor to the interim government, Yunus has taken steps that many observers describe as “making the right moves.” He has reached out to religious minorities, reassuring them of their rights and protections as citizens. He has also emphasised the need for institutional reforms to strengthen the foundations of democracy. However, his primary task remains ensuring that elections are held promptly, allowing a duly elected government to take charge without unnecessary delays.

Yet, the road ahead is fraught with challenges. Holding a free and fair election, particularly one that is free of violence, will be no easy feat. Bangladesh’s history is riddled with election-related violence, often with minorities being targeted as scapegoats. Yunus is acutely aware of this, but his government’s actions thus far have been less than reassuring.

Recent moves by ministers in the Yunus cabinet have raised concerns about their priorities. Instead of focusing on the pressing issues of institutional reforms and providing relief to those affected by the devastating floods in Bangladesh, some ministers have indulged in reckless rhetoric, directing their anger towards India and blaming it for the floods. This diversionary tactic has not only been unhelpful but also irresponsible, especially as it distracts from the government’s failure to address the real issues facing the country.

Moreover, there has been a deafening silence from Yunus and his cabinet regarding acts of revenge against those associated with the Awami League. Supporters of the Awami League, including some of its leaders, have been brutally murdered in what appear to be targeted killings. Those heading key institutions, such as the Supreme Court, universities, and the police force, have also been targeted, although the military has been spared for now, as it is seen as an ally in the recent uprisings. However, this uneasy truce with the military may not last if the interim government fails to establish a coherent agenda and plan to lead the country towards elections.

As Islamist groups like the Hefazat and the Jammat sense an opportunity to assert their influence, the stakes for Bangladesh’s future could not be higher. In a report published in the Dhaka Tribune Hefazat’s Joint Secretary General, Maulana Azizul Haque Islamabadi, has been quoted as saying, “This unity, or a greater unity, will be of no use if we cannot unite in the battle of the ballots.” The Sunday meeting in Dhaka was not just a gathering; it was an endorsement of the coalition between these Islamist groups under the leadership of Jamaat chief Dr. Shafiqur Rahman. The news report also suggests that Islamabadi praised Rahman, saying, “The Jamaat Ameer has blessed everyone by bringing together the scholars of all Markaz.” Another leader of the Hefazat, Mufti Azharul Islam, commended Rahman for his piety, suggesting that his leadership could pave the way for the formation of an “Islamic state.”

It is worth noting that Hefazat is not merely an outside force; it is embedded within the very structure of the interim government. Senior Hefazat leader AFM Khalid Hossain, who serves as the Adviser for Religious Affairs, holds significant sway in Yunus’s cabinet. His presence, along with other Islamist figures, underscores the growing influence of these groups within the government.

For pro-reform groups and individuals, the fear of an Islamist takeover is not just paranoia; it is a real and present danger. Taufiq Islam, a youth activist, voices the concerns of many when he says, “A foothold in politics would mean the implementation of Islamic rules, such as Sharia law, however much it is antithesis to the very creation and idea of Bangladesh.” The cultural and linguistic identity that was at the heart of Bangladesh’s struggle for independence from both British and Pakistani rule now faces the threat of being eroded by the imposition of Sharia and other Islamic tenets.

The threat posed by groups like Hefazat-e-Islam is not just ideological; it is also physical. Hefazat has a history of using violence to advance its agenda, often targeting religious minorities, particularly Hindus. The violence that erupted following Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Bangladesh in March 2021 is a chilling reminder of Hefazat’s willingness to resort to brutality. Protests turned into violent riots, with attacks on a train in the eastern district of Brahmanbaria and the desecration of several Hindu temples.

Hefazat-e-Islam, an umbrella organisation of radical Islamists, has clashed with the Awami League government in the past. Formed in 2010, it rose in opposition to the sweeping reforms initiated by the military-backed caretaker government in 2008 and continued by the Sheikh Hasina government after it was elected in December 2008. According to liberal intellectuals in Dhaka, Hefazat has always been “anti-reforms.” Media reports describe it as coming together to oppose the National Women’s Development Policy Bill, which promised equal rights for women, and the proposal to repeal the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, which would have reduced the clergy’s influence in Bangladeshi politics.

Despite the significant changes made to the original secular Constitution during years of military rule, Islamist groups like Hefazat and Jammat have fiercely resisted any further reforms. They have also been vocal in their anti-India propaganda, brainwashing young minds and fuelling anti-India sentiment. Members of the interim government are said to have deep connections with Bangladeshi influencers and political activists who have spearheaded the “India out” campaign. These groups have been particularly active since the January elections and appear to have supporters and funders in the West, particularly in the United States.

The future of Bangladesh hangs in the balance. As Yunus navigates the treacherous waters of interim governance, the nation watches anxiously, torn between the promise of a secular, democratic future and the dark allure of an Islamic state. The coming months will be crucial in determining whether Bangladesh will uphold the ideals of its founding or succumb to the forces of radicalism that threaten to rewrite its history.