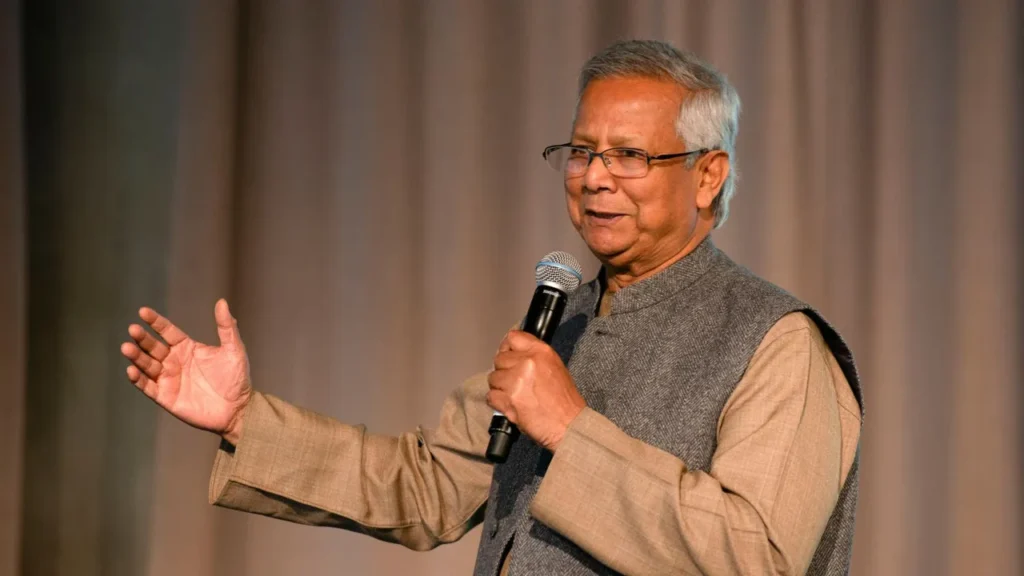

Various leaders in India have reacted differently to the statement made by Prof. Muhammad Yunus, head of Bangladesh’s interim government, during his recent visit to China. Yunus, many argue, has crossed a red line by stepping into India’s sovereign space—describing the Northeast as “landlocked” and claiming Bangladesh as the “only guardian of the Ocean” for the region while attempting to court Beijing for economic cooperation. This posturing is not new in Bangladesh’s internal politics, but Yunus has now elevated the discourse by bringing China into the equation.

Although the Indian government has not issued an official reaction, leaders from the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) have strongly criticised Yunus for dragging India into a bilateral discussion between Bangladesh and China. Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma condemned the remarks as “offensive” and “strongly condemnable.” Meanwhile, Sanjeev Sanyal took to X, questioning the significance of Yunus’ appeal to China based on the claim that the seven Northeast states are landlocked.

Pradyot Manikya, leader of Tripura’s Tipra Motha party, responded by advocating for India to establish an independent route to the ocean. “Time for India to make a route to the ocean by supporting our indigenous people who once ruled Chittagong so we are no longer dependent on an ungrateful regime,” he said on X. “India’s biggest mistake was to let go of the port in 1947 despite the hill people living there wanting to be a part of the Indian Union,” The Tipra Motha leader added. Congress leader Pawan Khera also criticised Bangladesh’s approach, calling it dangerous for the Northeast while questioning the Indian government’s foreign policy.

Assam CM Sarma further stressed the need for stronger rail and road networks connecting the Northeast to the rest of India. According to him, Yunus’ remark “underscores the persistent vulnerability narrative associated with India’s strategic ‘Chicken’s Neck’ corridor.” This 60 km-long and 21-22 km-wide Siliguri Corridor in West Bengal connects the Northeast to the rest of India while being surrounded by Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan.

Prof. Muhammad Yunus’ statement carries significant security and strategic implications, particularly as he has drawn India’s Northeast into the conversation in the context of China. The region is connected to the rest of India through the narrow ‘Chicken’s Neck,’ and by invoking this sensitive geography, Yunus—whose interim government is seen as leaning towards Pakistan and China while distancing itself from India—appears to amplify the vulnerability of this corridor.

There are strong concerns that the interim government in Bangladesh is collaborating with foreign interests seeking to destabilise the Northeast. The strategic importance of the Siliguri Corridor cannot be overstated—it is not merely a transit route but the very “lifeline of the Northeast.” Any suggestion of its disruption raises alarms about potential attempts to sever the region from the rest of India. Furthermore, Yunus’ reference to the Northeast as “landlocked” while promoting increased Chinese economic presence in the region is likely to heighten anxieties within Indian policy circles in New Delhi.

The interim government’s growing disconnect with the Bangladesh military, coupled with its increasing reliance on Islamist fundamentalist groups, raises questions about whether Yunus’ statements are a calculated political move to maintain relevance. His remarks, whether strategic or politically motivated, highlight the fragile geopolitical environment and the potential for external actors to exploit regional vulnerabilities.

Critics of Yunus and the interim government argue that the statement made in Beijing was “a way to stay afloat,” particularly since China reportedly does not trust Yunus or his government. “They will maintain necessary bilateral ties, but they don’t trust Yunus and consider him an American puppet,” said Isfaq Hussian, a left-leaning political worker in Bangladesh. According to him, Chinese support has been decreasing, and given the Bangladesh military’s dissatisfaction with Yunus, Beijing is not keen on making new investments.

Observers in Bangladesh who have been quietly assessing the unfolding situation believe that such rhetoric from Yunus and his interim government is more of a “political campaign” than a reflection of real capabilities. “Bangladesh on its own does not have the means to execute anything of significance, so whatever they are thinking must have external backing,” said Hussian, with an implicit reference to Pakistan.

This is not the first time that the interim government has engaged in provocative posturing. Mahfuz Alam, Bangladesh’s de facto interim information minister known for his incendiary remarks, posted a controversial map on Facebook on December, depicting parts of West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam as belonging to Bangladesh. Following backlash, he deleted the post. India had lodged a strong protest through its Ministry of External Affairs, stating, “We would like to remind all concerned to be mindful of their public comments. While India has repeatedly signalled interest in fostering relations with the people and the interim government of Bangladesh, such comments underline the need for responsibility in public articulation.”

Despite Yunus’ claims about the Northeast being “landlocked,” the region has been a source of significant economic benefits for Bangladesh for decades. During Bangladesh’s independence movement, the Northeast provided shelter to millions of refugees and served as a base for Indian forces. Since then, India’s Northeast has been a crucial point for trade and energy supply to Bangladesh.

Geographically, Bangladesh is indeed closer to the seven northeastern states than the rest of India, making it a natural trade partner. Tripura, Assam, and Meghalaya have long-standing trade relationships with Bangladesh, with demand for Bangladeshi products growing steadily in other Northeast states. If leveraged wisely, this proximity presents a significant market opportunity for Bangladeshi businesses.

The expansion of bilateral trade has mutually benefited both regions. Bangladesh operates border trade points with Tripura, Assam, and Meghalaya, facilitating the entry of Bangladeshi goods into Northeast India. Media reports have quoted the Assistant High Commissioner of Bangladesh in Guwahati, Shah Mohammad Tanveer Mansoor, as acknowledging the growing trade ties, highlighting the demand for packaged food, cement, plastics, and clothing from Bangladesh in the Northeast. He emphasised the need for improved connectivity and port management to further boost trade.

Assam Chief Minister Sarma also recognised the potential for economic cooperation, stating, “There is a lot of potential in the commercial field between Bangladesh and India’s northeast. There is an MoU for the supply of diesel from Assam to Bangladesh. We are putting emphasis on developing mutually beneficial economic relations.”

Trade between Bangladesh and the Northeast has been robust even without Chinese intervention. Bangladesh has long relied on Meghalaya’s coal to sustain its brick kiln industry in Sylhet. Before the National Green Tribunal’s ban on rat-hole mining, Meghalaya exported around 7.5 million metric tonnes of coal to Bangladesh, with Garo Hills alone contributing around 1.5 million metric tonnes.

According to a 2022 report by the South Asia Monitor in the 2019-20 fiscal year, Bangladesh’s exports to the Northeast amounted to over 367 crore Bangladeshi taka, up from 40 crore the previous year. The report adds that in contrast, imports from the Northeast to Bangladesh stood at 390 crore taka, compared to 472 crore in the previous year. Northeast India exports a diverse range of goods such as coal, ginger, onions, chilies, poultry feed, eggs, textiles, sugar, auto parts, fruits, and engineering products to Bangladesh, alongside commodities like cotton, tea, limestone, petroleum products, and minerals.

Given this long-standing history of trade and interdependence, Yunus’ attempt to portray the Northeast as “landlocked” and in need of Chinese economic intervention is both misleading and unnecessary. The Northeast’s connectivity is already deeply intertwined with Bangladesh, and the idea of bringing China into the equation seems more like a geopolitical gambit than an economic necessity.

Is Yunus merely playing to external interests that seek to undermine India’s position in the region? With his government’s diminishing legitimacy and its growing reliance on forces hostile to India, his remarks raise more questions than answers. Who truly stands to gain from this narrative—Bangladesh, or those who see the Northeast as a pawn in a larger geopolitical contest?