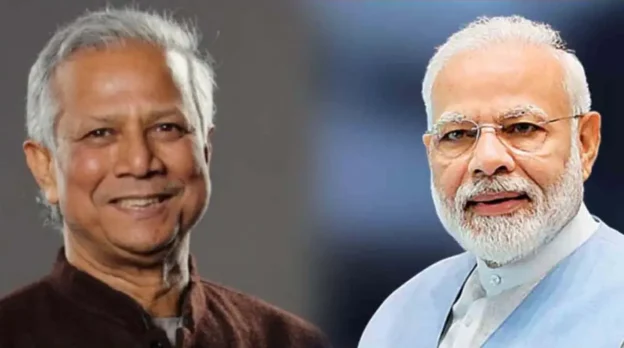

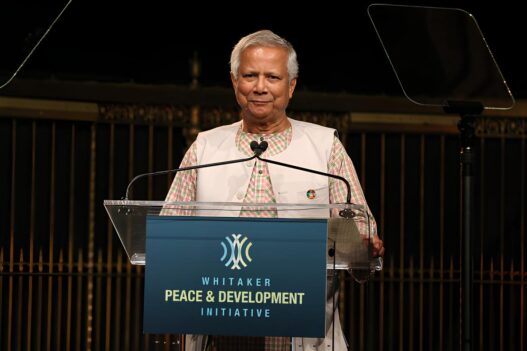

In a startling shift in regional discourse, Bangladesh’s interim leader Professor Muhammad Yunus recently described India’s Northeast as “landlocked,” proclaiming Bangladesh as the region’s “only guardian of the Ocean.” These remarks—part of an overture to court Beijing for economic cooperation—have stirred sharp criticism across diplomatic circles, both in India and within Bangladesh. The statement has been branded “reckless diplomacy” by Bangladeshi commentators and “strongly condemnable” by senior Indian officials, fuelling anxieties about a deeper strategic realignment in South Asia.

More critically, Yunus’s comments have reignited the vulnerability narrative surrounding the Siliguri Corridor—India’s narrow land bridge to the Northeast, hemmed in by Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. This slender, 60-kilometre-long and 20–22 km-wide strip—often termed the Chicken’s Neck—has long been a cornerstone of India’s strategic consciousness, but the fresh rhetoric from Dhaka, with Beijing looming in the background, has cast new urgency on its defence.

Former Chief of India Army’s Eastern Command Lieutenant General Rana Pratap Kalita, in a recent event hosted by The Borderlens in Guwahati, underscored the irreplaceable importance of this sliver of land. Describing the corridor as the “lifeline of the Northeast,” he warned that its fragility lies in stark contrast to its necessity—connecting a region that shares 99% of its borders with five countries, and only 1% with mainland India. “Any disruption—be it military or logistical—can sever the Northeast,” he cautioned, placing the region’s security at the core of India’s national interest.

This concern is echoed by China expert Prof Srikanth Kondapalli of Jawaharlal Nehru University, who views the Bangladesh-China axis, particularly in the context of Myanmar, as a growing flashpoint. While he affirms that India has acquired greater deterrence post-Galwan and could retaliate with long-range, stand-off weapons, he warns that the strategic calculus may be shifting. “India might no longer rely solely on defensive posturing,” he noted, suggesting a doctrinal pivot to deterrent strikes deeper into enemy territory.

Kondapalli also pointed to China’s ongoing deployment of psychological, technological, and non-kinetic warfare. Despite these hybrid threats, he insisted, “India has not succumbed.” He highlighted the potential of counter-technologies—such as electromagnetic weapons—and stressed that New Delhi’s strategic patience is not to be mistaken for weakness.

This hardening of posture is visible on the ground. India’s recent deployment of the S-400 Triumf air defence system to the Siliguri Corridor signals a decisive shift. With its 400-km interception range and multi-target tracking capabilities, the Russian-built system strengthens India’s shield against potential aerial threats emanating from both China and Bangladesh. Complementing this move is the operational readiness of a Rafale fighter squadron at Hashimara Airbase—equipped with Meteor air-to-air and SCALP air-to-ground missiles, forming a potent second line of response.

New Delhi’s escalated vigilance isn’t without cause. Reports suggest that Bangladesh is actively exploring the establishment of a Chinese-backed airbase in its northern Lalmonirhat district, perilously close to Siliguri. Equally alarming are increased sightings of Bangladeshi surveillance drones along the border. In one recent incident in South Tripura’s Ballamukha, a drone equipped with a camera landed just 300 metres from the international fence, sparking fears of targeted reconnaissance. Another episode involving a Bayraktar TB2 drone triggered a diplomatic response after it flew near Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram, violating agreed protocols.

With Dhaka now operating up to six Bayraktar drones—procured from Türkiye—and reportedly eyeing 32 JF-17 Thunder jets (a joint Pakistan-China platform), Indian analysts view these acquisitions as signs of a growing tactical and strategic shift. “Bangladesh’s military modernisation, supported by adversaries like China and Pakistan, has consequences far beyond Dhaka’s borders,” warned one senior defence official.

For General Kalita, the situation is further complicated by the growing footprint of Chinese nationals in Bangladesh’s Rangpur division near Dinajpur. Ostensibly involved in infrastructure projects, their presence near the Siliguri Corridor raises concerns about possible dual-use facilities. “The Chinese have been persistent in inching closer—whether through western Bhutan, eastern Nepal, or northern Bangladesh,” General Kalita observed. “A map of Chinese movements will draw a near-perfect encirclement around Siliguri.”

Recent media reports suggest a convergence of Chinese interests in the Chumbi Valley, a dagger-like projection into India’s neck from Tibet—adding further strategic weight to General Kalita’s assessment. The Indian Army, too, has not underestimated this growing threat. Former Army Chief General Manoj Pande had categorically described the corridor as “sensitive” and “critical,” echoing the sentiment that has long informed New Delhi’s eastern defence doctrine.

Even academic voices like Prof Binayak Sundas of North Bengal University see the current moment as a culmination of two festering fears: demographic shifts due to migration and an encroaching China. He noted that while these issues have existed for decades, Bangladesh’s recent political rhetoric makes them more relevant than ever. Kondapalli agreed that though dispersed, the demographic factor could pose long-term problems, while China’s calculated moves—masked under regional diplomacy—present an immediate challenge.

Citing the Chinese military treatise Unrestricted Warfare, Kondapalli warned against expecting periods of peace in a full-spectrum strategic environment. The Chinese doctrine, he explained, champions continuous contestation—across military, economic, technological, and information domains.

This evolving reality leaves India with little room for complacency. The apparent pivot by Dhaka, under leaders like Yunus eager to burnish nationalist credentials or attract Chinese capital, could create openings for Beijing to sow disruption. As some scholars suggest, a coordinated strategy involving China, Pakistan, and Bangladesh could be aimed at creating “social disruption” and testing India’s eastern resolve.

Despite historical and cultural ties with Bhutan and Nepal—nations that have, for the most part, resisted Chinese overtures—India must now prepare for a complex, multi-layered security environment. The geography around Siliguri leaves no margin for error. With over one million vehicles using the corridor daily, transporting more than 2,400 metric tonnes of goods and contributing ₹142 crores in daily revenue, any disruption would come at an extraordinary economic and strategic cost.

The Siliguri Corridor is no longer just a topographical bottleneck—it is now a geopolitical fault line. And in this emerging battlefield of influence and encirclement, India’s choices will shape not just regional balance, but the very idea of secure connectivity between its heartland and its Northeast.