The Eastern Himalayas consist of areas that presently fall under the jurisdiction of Nepal, India, Bhutan and China (Tibet). It is home to multiple communities, who follow a plethora of religious beliefs and practices, that includes Tibetan Buddhism.

Prior to the 1950s Chinese occupation of Tibet, this belief system was a mode of gaining legitimacy by the ruling elites in the Tibetan regions. One sees this with the establishment of the ‘Ganden Phodrang’ government in the 1640s, with the line of the reincarnated Dalai Lamas ruling over Tibet through the principle of ‘cho-si sungdrel’, a blend of religion and politics. Around the same period, Tibetan Buddhism was employed as a tool of political dominance by the Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, another Tibetan reincarnate who unified and ruled over Bhutan. Even the erstwhile Sikkimese Namgyal dynasty, established in 1642, relied on Tibetan Buddhism to strengthen their legitimacy over Sikkim.

Tibetan Buddhism forms the common thread stitching what has been termed as ‘cultural Tibet’ that includes major portions of the Himalayas stretching from Ladakh, Lahoul-Spiti, Nepal, Darjeeling Hills in India’s West Bengal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Tawang in India’s northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh. The form of Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayas is Vajrayana or tantric Buddhism, that came to these regions in the 8th century AD. Tibetan Buddhism has four major schools – Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and Geluk. These are further divided into sub-schools, who have monasteries and communities spread across Tibet and the Himalayas.

The individual responsible for the spread of this school of Buddhism in the Himalayas is the semi-mythical Guru Padmasambhava, an Indian tantric Buddhist adept, who was born in the Swat valley, current location of which is termed as modern day Pakistan. He founded the Nyingmapa school of Tibetan Buddhism. The seven-line prayer supplication to Guru Padmasambhava, a terma or hidden treasure, revealed by Guru Chowang or Chokyi Wangchuk, a terton (treasure revealer) of the 10th century AD, mentions how the Indian tantric master was born in the north-west of the land of Orgyen or Oddiyan, corresponding to modern Swat valley.

At present, the Saidu Sharif monastery is located in the Swat valley, which used to receive pilgrims from Tibet and the Himalayas. This narrative has been mentioned by Italian Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci (1940), who writes about his discovery of two texts in western Tibet which are guidebooks for pilgrims to the Swat valley.

Even in 2016, around thirteen monks from Bhutan visited and worshipped in the monasteries in Swat valley, Pakistan. According to Tsewang Penjore, the head monk of the oldest monastery in Bhutan, the Swat valley is the “fountain spring of Vajrayana Buddhism and as Guru Padmasambhava is the son of this soil, who is the most respected Guru in Bhutan, we are privileged to visit here”. Here, Guru Padmasambhava emerges as the common link that connects different parts of the Himalayas.

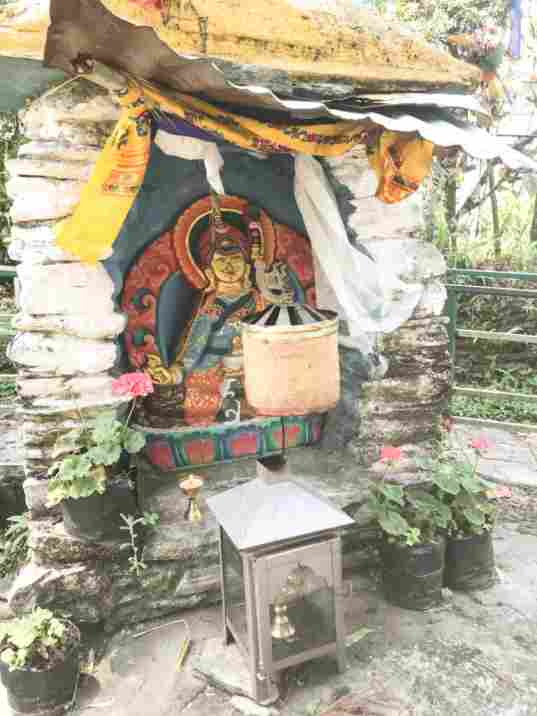

Interestingly, the tantric master had traversed across the length and breadth of the Himalayas, sowing the seeds of the Buddha dharma. The mode through which the master established Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayas was through the act of ‘taming’ local, autochthonous deities of the land, binding them in the service of Buddhism. As Cathy Cantwell and Robert Mayer writes, Guru Padmasambhava emerged as the ‘figure par excellence who tamed and controlled all indigenous deities in the name of Buddhism. Padmasambhava is by the same token the figure who made it safe for converts to abandon their ancestral gods without fear of divine retribution’.

The idea of ‘taming’ of local deities is central in understanding the spread of Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayas. In ‘Barche Lamsel’, the prayer to Guru Padmasambhava, which removes all obstacles from the path, ‘taming’ of local gods and goddesses is a central idea. The prayer is a ‘terma’ revealed by Chokgyur Dechen Lingpa (1829-1870), a ‘terton’ or treasure revealer from the foot of the ‘Danyin Khala Rango’ rock in Tibet.

The prayer mentions how Guru Padmasambhava bound the twelve Tenma goddesses under oath in Palmotang, upon the Khala pass of Central Tibet he bound the ‘Fleshless White Glacier’. He bound the Thanglha Yarshu before Damsho Lhabu Nying. The Barche Lamsel prayer further elaborates how some of these ‘tamed’ gods and goddesses offered the core of their life force, some undertook to guard the Buddhist teachings and some pledged to serve the Indian master. They are the ‘chos-kyong’ or dharmapalas, who according to Christopher Bell, are propitiated by laypersons for achieving worldly desires. He writes ‘as for the types of spirits that become protector deities, they include a mix of Tibetanized Indian divinities, such as yakṣas (gnod sbyin), nāgas (klu), and rākṣasas (srin po), as well as strictly indigenous gods, such as rgyal po, btsan, and dmu’.

The propagation of the protector deities reveals the mechanism through which Vajrayana Buddhism flourished in Tibet and the Himalayas. While the process of ‘taming’ of local gods does involve a degree of subjugation, as they are positioned at a lower hierarchy, it also invokes the co-option of the ‘local’, providing them with a position and a degree of autonomy.

As mentioned above, Padmasambhava plays a significant role in the process of Buddhacisation, especially in the Himalayas. He received teachings in Nalanda university and practiced in sacred charnel grounds, including Sitavana, the cool grove charnel ground near Bodh Gaya (nekor.org). According to Jacob Dalton, who has worked extensively on tantric ritual, Nyingma religious history, and the Dunhuang manuscripts, the Guru then proceeded to Nepal, where in the caves of Yanglesho, near Kathmandu, he gathered the texts of Vajra Kiliya (Dorje Phurba), an esoteric tantric practice and tamed local deities.

In the nearby Asura caves, he bound the twelve Tenma goddessess, turning them into protectors of the Buddha dharma (rigpawiki.org). Guru Padmasambhava and his consort Mandarawa, received immortality from the Buddha Amitayu, while meditating in the caves of Maratika, located in Haleshi, Nepal. While he was in Nepal, the Indian master received an invitation from the Tibetan king Trisong Detsan to aid in the construction of Samye, Tibet’s first Buddhist monastery.

Guru Padmasambhava tamed the local gods, who were obstructing the construction of the monastery. His tantric prowess was responsible for his success in introducing Buddhism in Tibet. In the borderlands, on his way to Tibet, he also tamed a series of gods and goddesses, binding them to become protectors of the dharma.

Anthropologist Geoffrey Samuel writes ‘as Padmasambhava travelled from his meditation-cave in Nepal through Tibet to Samye, he subjugated the local deities through his Tantric power and forced them to take oaths of obedience to the Dharma’. He further elaborates how this is a ‘critical and central episode for the entire conceptual structure of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet, since the ability of later generations to control the deities through Tantric Buddhist ritual and so to secure the prosperity and wellbeing of the Tibetan people is premised on this initial submission of the deities to Padmasambhava’.

In many cases, Padmasambhava came back from Tibet to the Himalayan borderlands to subjugate local deities. Tibetologist and Tibetan Buddhist writer Glenn H Mullin , for instance, talks about how the Indian tantric master travelled to Lo Monthang in Nepal from Tibet, performed rituals to bind the Mustang land spirits to Dharma, and then returned to Samye and successfully completed the building efforts there. On similar lines, there are several sites in the eastern Himalayas frequented by Guru Padmasambhava, where he indulged in the act of ‘taming’ local deities, turning them into ‘sungmas’ of the Buddha dharma. What is interesting, is how the Indian saint also transformed the landscape in the Himalayas, turning them into ‘hidden lands’ or ‘beyul’.

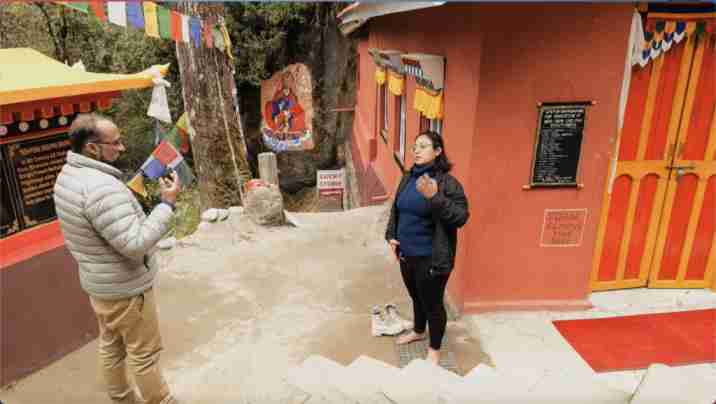

Photo credit: The Borderlens

Amy Corbin writes ‘the beyul are large mountain valleys, sometimes encompassing hundreds of square kilometers, found in the Buddhist areas of the Himalaya in Nepal, Tibet, India and Bhutan. They originate from the beliefs of the Nyingmapa sect of Tibetan Buddhism, which has a rich tradition of respect for natural sites.

According to ancient Buddhist texts, the beyul were preserves of Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, who introduced Buddhism to Tibet and founded the Nyingmapa tradition in the eighth century. Corbin explains how “information on their locations was kept on scrolls hidden under rocks and inside caves, monasteries and stupa (shrines).” She goes on to add that, “Some beyul are now inhabited, others are occasionally visited by spiritual seekers and adventurers, and some are still unknown. The total number of beyul, discovered and not, is often said to be 108”. These sacred hidden lands were to be discovered by the future reincarnations of the twenty-five main disciples of Guru Padmasambhava. Most of them were reborn as treasure revealers or ‘tertons’, who had the power to open these lands. The beyuls are spaces of refuge from various calamities for believers in the near future.

Beyuls in the Eastern Himalayas – hidden lands of Padmasambhava

The Eastern Himalayas have several of these ‘hidden lands’, primary among them being Sikkim also known as Beyul Dremojong and Pemako, which is located near the border with Arunachal Pradesh. Beyul Dremojong or Sikkim was opened by Rigdzin Gödemchen Ngodrub Gyeltsen (1337-1409), known simply as Rigdzin Gödem (nekhor.org). He is most well known as the terma revealer of the Northern Treasures (Changter).

Guided by Guru Padmasambhava in both visions and dreams, Rigdzin Gödem went on a hazardous journey in search for the beyul Dremojong, ‘the Valley of Fruits,’ which later became known as Sikkim. He first entered the hidden land through the snow covered high northwest pass known as Chorten Nyima, and opened the gate of Sikkim to the Land of the Snows. His visionary insight was monumental in establishing Sikkim as a sacred landscape, a true beyul that would serve as a spiritual refuge for many Tibetans in the years to come.

Later, in 1646 the renowned treasure-revealer Lhatsün Namkha Jikmé (1597-1653) journeyed to Sikkim, where he tamed the local spirits and thus fully established the sacred land in the Dharma (nekhor.org). Along with two other monks, Kathok Kuntu Zangpo and Ngadak Sempa Chenpo, they crowned the first Chogyal or king of Sikkim. The idea of Sikkim as a ‘hidden land’ could have emerged with the rise in conflict in Tibet in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially the sectarian strife between the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The conflict was further accelerated with a few schools being provided military support by the Mongolians. In most cases, the Nyingmapa followers were persecuted and had to take refuge in the south-lands of Tibet. It is under such circumstances that Guru Padmasambhava’s ‘hidden lands’ became a source of safety and a haven for them.

The idea of a beyul has remained prominent in the 19th-20th centuries, with numerous ‘tertons’, practitioners and the devout embarking on an adventure in search of the ‘hidden lands’. In the late 1950s, a terton Tulshik Lingpa, hailing from eastern Tibet came in search of the legendary beyul in Sikkim. His quest attracted a large following, who accompanied him to the slopes of the high mountains in Sikkim and eastern Nepal.

The other famous beyul in the eastern Himalayas is Pemako in southeastern Tibet, which was first mentioned in the prophesies of 17th century master Jatsön Nyingpo. Over the course of two hundred years, the sacred land was gradually made more accessible until becoming fully opened by Dudjöm Lingpa in the late 19th century (nekhor.org). Pemakoe is a picturesque place located near the great bend of the Tsangpo river, which flows into India as the mighty Brahmaputra.

In Bhutan, the Guru is credited with creating a number of beyuls or hidden lands. The ‘dragon kingdom’ had hosted Guru Padmasambhava in the eight century AD, when in 810 AD he was invited by Sindhu Raja of Bumthang to subdue the local deity, Shelgin Karpo, who had snatched the king’s life-soul making the king ill. Guru Padmasambhava came from Nepal and entered Bhutan via Nabji Korphug in Zhemgang[MOU2] . He visited Bhutan several times and laid the foundations for the growth of tantric Buddhism and also created numerous ‘beyuls’.

Professor Robert Barnett, writer and researcher on modern Tibetan history and politics is of the view that the beyul Khenpajong in northern Bhutan is one that received some media coverage in recent times as the Chinese had illegally constructed villages in the region. Another popular beyul in Bhutan is Langdra in Wangdue Phodrang, where Padmasambhava had tamed the local deity, who took the form of a bull, but was subdued by the master and turned into the guardian deity and protector of the dharma. The entire Bumthang valley is seen as a beyul, a hidden land that had been described as such by the Nyingmapa master Lonchen Rabjam (Jenkins 2020). According to Kinga Gyaltshen, Guru Padmasambhava visited eastern Bhutan and blessed Ajaney valleys, on the borders of the present day Mongar and Lhuntse districs, into beyuls. Even the Haa valley, bordering Sikkim is deemed as a beyul of Padmasambhava.

The trails of the Lotus Born in the Eastern Himalayas

The presence of beyuls or hidden valleys in the eastern Himalayas are proof of the activities of the Indian tantric master who brought Vajrayana Buddhism to these spaces, along with this, there are also numerous sites associated with him that provide evidence of the trails undertaken by the lotus-born in the Himalayas. There are a multitude of places, converted into pilgrimage spots in the eastern Himalayas associated with Guru Padmasambhava.

In Sikkim, he had visited and consecrated four caves, which are located in four cardinal directions from the Tashiding Monastery in west Sikkim. According to Buddhist texts, Tashiding is the navel or central point of Beyul Dremojong or Sikkim (Outlook Traveller 2021). These four caves are Sharchog Beyphug in the east, Nub Dechenphug in the west, Lho Khando Sangphug in the south, and Jhang Lhari Nyingphug in the north. These caves were spots where the Guru meditated and hid several sacred relics. In these sites, there are numerous signs left by the ‘lotus-born’, which in the case of Lho Khando Sangphug is an impression in the roof of the cave, which is said to be the mark of Guru Padmasambhava’s crown from the days when he meditated here (Outlook Traveller 2021).

Guru Padmasambhava had also broken a bridge near the cave preventing a demoness from crossing the river. Apart from these four primary caves there are other caves where the master had meditated and gained deeper spiritual insights. Below the Tashiding monastery, located in west Sikkim is a cave termed as Drakar Tashiding (white rock) where Guru Padmasambhava had blessed the water that emerges occasionally from the rocks.

A cave above the sacred Khecheopalri lake, near Pelling, west Sikkim is also a site where the master had meditated. According to Professor Jinpa, the sacred Mt. Kangchendzonga, third highest peak in the world is associated with Guru Padmasambhava. He had his vision of the mountain on his way to Tibet passing through Nepal, which was the abode of the Tsering chenga or five sister goddesses who were bound by the master to serve as protectors of the dharma. In north Sikkim, the Gurudongmar lake is a sacred water body linked to Padmasambhava.

Moving further east, in Bhutan, numerous sites (caves, lakes and other natural features) are associated with Guru Padmasambhava. The most prominent one is the Paro Taktshang, located in eastern Bhutan. Popularly known as the ‘tiger’s nest’, it is a prominent site for pilgrims and tourists alike. Here, the Indian tantric saint taking a fearful form known as Guru Dorje Drolo, had flown on the back of a tigress.

According to legend, the Tibetan consort of Guru Padmasambhava, Yeshe Tshogyal is supposed to have taken the form of the tigress. Paro Taktshang is one among the thirteen taktshangs caves where Padmasambhava is supposed to have meditated. In 1692, a temple complex was built around the cave by Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye and it is believed that Guru Padmasambhava had meditated in the cave for three years, three months, three days and three hours in 8th century (originalbuddhas.com).

The lotus born had visited Bumthang after being invited by the local ruler Sindhu Raja, who wanted the local deities to be subdued by the master. Padmasambhava meditated in Drakmar Dorje Tsegpa, where he left the imprint of his body. It is here that the Indian master tamed the local deity Shelging Karpo, who had supposedly stolen the life force of the Sindhu Raja. Guru Padmasambhava bound the deity to become a protector of the Dharma.

In Bumthang, the tantric master took Monmo Tashi Khudren, a daughter of the Sindhu Raja as his consort. According to oral account Guru travelled to Bumthang from south of Trongsa via Buli and Shingkhar as there are foot prints and body prints along Chamkhar river below Chhumey, the present Zhuri village (Dorji 2016) While Guru Padmasambhava founded numerous sacred sites in Bhutan, he also consecrated the famed Mebar Tso. The famous 15th century terton from Bhutan, Pema Lingpa had revealed ‘ter’ or hidden treasures from the lake (Maki 2011).

According to Kinga Gyeltshen, Guru Padmasambhava visited Bhutan thrice. During these visits, the tantric master visited and blessed several sites. According to oral accounts Guru travelled to Bumthang from south of Trongsa via Buli and Shingkhar as there are foot prints and body prints along Chamkhar river below Chhumey, the present Zhuri village. An interesting idea that emerges from the three visits of Guru Padmasambhava to Bhutan is how during the 7th-8th centuries, information regarding the presence of a tantric master whose prowess included subduing spirits was available. The travels of the great Indian master in the Himalayas can be understood as an example of early trans-Himalayan connectivities. The second and third visits were via Tibet. Another site in the eastern Himalayas visited by Guru Padmasambhava is Tawang, where the saint had meditated in a ‘taktshang’ cave, which presently has a temple dedicated to the Guru Padmasambhava.

Conclusion

The 8th century Indian master, renowned as Padmasambhava (lotus-born) established Vajrayana Buddhism in the Himalayas. Due to his immense spiritual and religious contributions to the diverse communities in the region, the saint is more popularly referred to as ‘Guru Rinpoche’ or the precious master. He is termed as the second Buddha by followers of Tibetan Buddhism and for numerous Himalayan people he occupies a central place in their altars.

Kinga Gyeltshen mentions how Guru Padmasambhava’s ‘multiple visits to Bhutan have significant impact to the Bhutanese society, as his teachings and contributions to Buddhist civilization in Bhutan holds central place in Bhutan’s religion and history’. Guru Rinpoche is the patron saint of Sikkim, with the Sikkim state government observing the birth anniversary of Guru Padmasambhava as Thrunkar Tshechu (northeasttoday.in). The Indian master’s birthday is a national holiday in Bhutan, where religious services are held in different monasteries in Bhutan. In 2021, on the birth anniversary of Guru Rinpoche, India gifted a statue of Buddha to Bhutan (WION 2021).

Guru Rinpoche and his activities can be seen as an example of trans-Himalayan interactions. The semi-mythical figure was born in the Swat valley, which lies on the edges of the western Himalayas while his religious and spiritual missions took him to the far corners of the eastern Himalayas. He received his ‘siddha’ in the caves near Kathmandu, corresponding somewhat to the central Himalayas, while the eastern Himalayas were one of the many spaces where he put his ‘siddha’ into action. This is seen with him creating numerous ‘beyuls’ or hidden lands, taming numerous local deities, binding them to become protectors of Buddhism and also consecrating a multitude of sacred sites in the region.

Various communities in eastern Nepal, Sikkim, Darjeeling hills, Bhutan and Tawang revere the precious master. This is a reason why the Nyingmapa (school founded by Guru Rinpoche) and the Kagyu school have more followers from the local ethnic groups in the region. The acceptance of the teachings of Guru Rinpoche among the diverse groups in the Himalayas reveals the adoption of local ideas and norms by the master, making them a larger part of the Tibetan Buddhist cosmology. One can erect a hypothesis that the Tibetan Buddhism as we know today, received its formative values and norms in the Himalayas before taking roots in Tibet, in which Guru Padmasambava has played a major role. It also reveals the fluidity present in Vajrayana Buddhism, in which Guru Padmasambhava played a mighty role.

in the Upper Subansiri district of Arunachal Pradesh. Photo Credits: Bidhayak Das